The latest query to land in the Whisky Professor’s inbox questions the difference between worm tubs and shell-and-tube condensers. Do they really make a difference to the flavour of new make spirit? Indeed they do, as the Prof explains.

Dear Professor,

While I now realise that worm tubs don’t actually contain worms, I’m still confused about the difference between these and shell-and-tube condensers. Why do some distilleries still use the former, while most have switched to the latter? Is it to do with flavour? I’d be grateful for any help you can offer.

Stephen Grant, Edinburgh

Flavour focus: The Whisky Prof explains how worm tubs and shell-and-tube condensers affect flavour

Dear Stephen,

In short: yes. Worm tubs and shell-and-tube condensers do have an impact on new make spirit character. In fact, they can have a significant one. It all comes back to our old friend copper, which makes this an excellent follow-on question after our last venture into whisky-making.

As you may recall, in that discussion we saw how the length of the interaction between alcohol vapour and active copper helps to dictate whether a new make spirit is light or heavy. The longer the ‘conversation’, the lighter the spirit will be. The same thing happens in the condensing system.

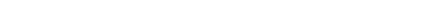

From the earliest days, distillers knew that immersing the end of the still in cold water would turn the vapour back into liquid. This could be as simple as having it coiled in a barrel filled with water, or running the pipe through a stream.

The worm tub as we know it was invented by the German chemist Christian Ehrenfried Weigel in 1771. He designed a system in which cold water was continuously pumped into the bottom of the tub and hot water removed from the top. Inside this tub was the worm itself (‘worm’ is the old English term for serpent, the original name for the coiled tube).

Today, the worm is a continuation of the lyne arm, which extends through the exterior wall of the distillery, wraps itself inside the tub and then runs to the spirit safe.

At first sight it is easy to think that there is a significant amount of copper in a worm. In fact, the opposite is the case. Not only does the diameter of the pipe steadily decrease, but the worm tub is in a cooler environment than inside the still house, while the constantly upwelling cold water ensures that condensing is quick. As a result, the spirit is heavy – often with (desirable) sulphur elements.

The effect of worm tubs on spirit character was most notably observed when Dalwhinnnie removed its worms and replaced them with shell-and-tube condensers. The new make spirit character (heavy and sulphury) changed immediately, so worms were reinstalled.

Worm tubs: Talisker is one of just 16 Scotch distilleries that still uses worm tubs

Distillers can, however, play a variety of tunes on worm tubs to help create different characters. If the flow of cold water into the tub is rapid, then condensing will take place quickly, resulting in a heavy, sulphury spirit. Craigellachie, Glenkinchie and Speyburn are good examples of this.

Some distilleries – Mortlach, for example – spray cold water onto the lyne arm just before it descends into the worm. This speeds up condensing even more and helps to create the distillery’s meatiness.

If the flow rate of the water is slow, then the worm tub heats up and prolongs the interaction between vapour and copper. This will help to make a lighter style of spirit – though this is relative as it will still be heavier than a ‘light’ spirit made in a distillery with shell-and-tube condensers. Distilleries which do this include Glen Elgin, Oban and Royal Lochnagar.

Again, Dalwhinnie was important in understanding this. The distillery’s original worm tubs were rectangular, cast-iron vats. As the first thing visitors would see when arriving at the distillery would be the worms, the replacements were in a more aesthetically-pleasing, washback-style shape. Because the water flowed in a different manner in these, the spirit character, while sulphury, was still different to that from the old worm tubs, so the flow rate had to be adjusted.

Worm tubs are now unusual. Of the 118 operational Scotch whisky distilleries, only 16 have them: Ballindalloch, Balmenach, Benrinnes, Glenkinchie, Cragganmore, Craigellachie, Dalwhinnie, Edradour, Glen Elgin, Mortlach, Oban, Old Pulteney, Royal Lochnagar, Speyburn, Springbank and Talisker.

New make spirit: Worm tubs tend to produce a heavier, sulphury spirit

That means that every other distillery has a shell-and-tube condensing system in place. In this, a bundle of around 100 copper tubes, through which cold water flows, are contained within a copper shell. When the vapour hits the cold tubes, it condenses into spirit.

Because there is a huge amount of available copper, the spirit produced from a shell-and-tube set-up tends to be light in character. Glen Ord, for example, runs hot water through the condensers, helping to prolong the copper conversation even further, and producing an intense, grassy character.

Once again, though, there are exceptions to this rule, and distillers have worked out ways to produce a heavier style from a shell-and-tube configuration by reducing the impact of copper. Inchdairnie, for example, runs cold water through its shell-and-tube condenser to get its heavy make, and warmer water to get a lighter character.

Having condensers outside the hot still house (Benromach, for example) is another way of building in some heaviness. An even simpler solution – removing the copper altogether – is now being used at a number of sites. Ailsa Bay and Roseisle are both able to switch between copper and stainless steel condensers depending on whether they are making a light or heavy style, a method originally trialled at Dailuaine (they have since been removed).

The two systems have co-existed for longer than might be imagined. Shell-and-tube condensers were invented in 1825 by William Grimble and were in place in a number of Scotch distilleries by the 1880s when Alfred Barnard was on his journeys. He refers to them being in use at Glenugie, Dean (Edinburgh), Cameronbridge and Kirkliston.

Bowmore also had shell-and-tube condensers at this time, though they were used in conjunction with the worms. Glenmorangie had condensers fitted in 1886, probably at the suggestion of owner Edward James Taylor, who also introduced steam heating for the (new, tall) stills. The widespread move away from worm tubs gained traction after the Second World War.

Might worms make a partial comeback? Ballindalloch installed worm tubs in its aim of making an ‘old-style’ whisky, while Islay’s new Ardnahoe will also have worms – so we may see more as new distilleries are built.

I hope that this helps.

Prof

Do you have a burning question about Scotch whisky for the Whisky Professor? Email him at [email protected].